The Latin American Fertility Project

Computing Total Fertility Rates for Latin American and the Caribbean using census data

Is the fertility transition in developing countries explained by improvements in socioeconomic variables or is it better explained by the diffusion of new behaviours, values and attitudes regarding family size?

Cross-country evidence shows that there are strong correlations between variables such as income and fertility (the highest fertility rates are found in the poorest countries) or fertility and education (women with more years of education have fewer children). But regionally disaggregated data shows that these demographic processes do not fully reflect the improvements in socioeconomic conditions. Specifically, convergence in fertility rates is not always linked with convergence in economic development between regions, suggesting a weak relation between demographic outcomes and economic performance.

The case of Latin America and the Caribbean is an example of this. Despite a generalised decline in fertility, there were important socioeconomic differences among (and within) countries. However, studying the fertility transition in Latin American countries is challenging because the vital registration data is weak with high levels of under registration.

The idea of this project is to show how with the available data from IPUMS and Human Life-Table Database it is easy to calculate age-specific and total fertility rates to study the fertility transition in several countries. Although I provide open code to calculate Total Fertility Rates (TFR) by country over 14 years, it is possible to adapt the code to calculate the TFR by area of residence, level of schooling or the occupational status of the mother. It is also possible to include more censuses to obtain a broader period.

IPUMS, Human Life-Table Database and the Own Child Method.

I use census samples from 16 Latin American and Caribbean countries obtained from IPUMS and the corresponding life-tables from the Human Life-Table Database. I use all the countries that have available censuses and life tables in the 1970s because the fertility transition in this region started around 1960 for most countries, so I am able to observe the onset of the transitions from a comparative perspective.

The Own Child Method was developed in the 1960s to calculate fertility rates when, as in Latin America, birth registration data is incomplete or unavailable. It has been widely used to estimate fertility in historical censuses and for developing countries. The method is based on two key elements of the census: the recorded age of people in the household, and, when available, the relationship of each member of the household to the household head.

The Integrated Public Use Microdata Series - IPUMS used this method to create links between partners, and parents and children in all their census samples.

Once a pair of mother and child is identified, then one can calculate the Age-Specific Fertility Rate (ASFR) and Total Fertility Rate for several years (in this case for 14 years) using the data of children between 0 to 14 years old and mothers between 15 and 78 years old. For these estimations, the ASFR of each year is defined as the ratio between children born that year to women that are between 15 and 64 years old at each year. Given that maternal mortality is not visible in the census, the number of women at each year is adjusted by the probability of surviving using the corresponding life tables from the Human Life-Table Database for each country. Similarly, the number of children at each age is also adjusted. As the Human Life-Table Database provides abridged national tables, to obtain single-year survivorship probabilities I use the MORTPACK package from the United Nations. Finally, the number of children has to be adjusted by the proportion of children at each age that were not matched to their mother.

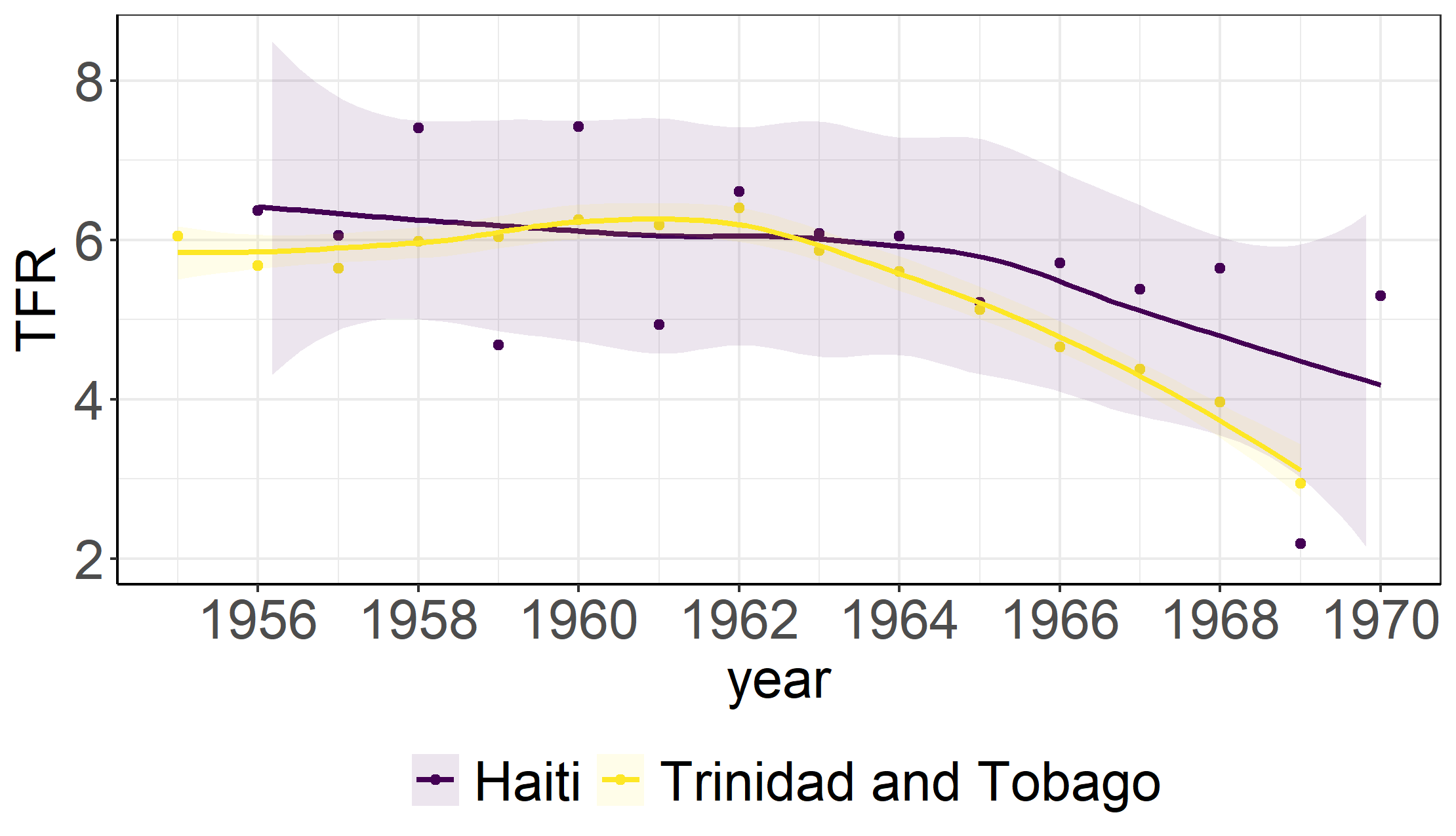

As for the caveats of the data and the methodology, it is important to consider that age heaping among older children reported in the census could result in considerable fluctuation (see for example the results from Haiti). Also, misreporting of the age of children that are about to turn one or two years old or unrecorded births and under-enumeration of zero-years-old could lead to underestimation of the total fertility rate in years that are closer to the date of the census

Fertility patterns in 1960s Latin America

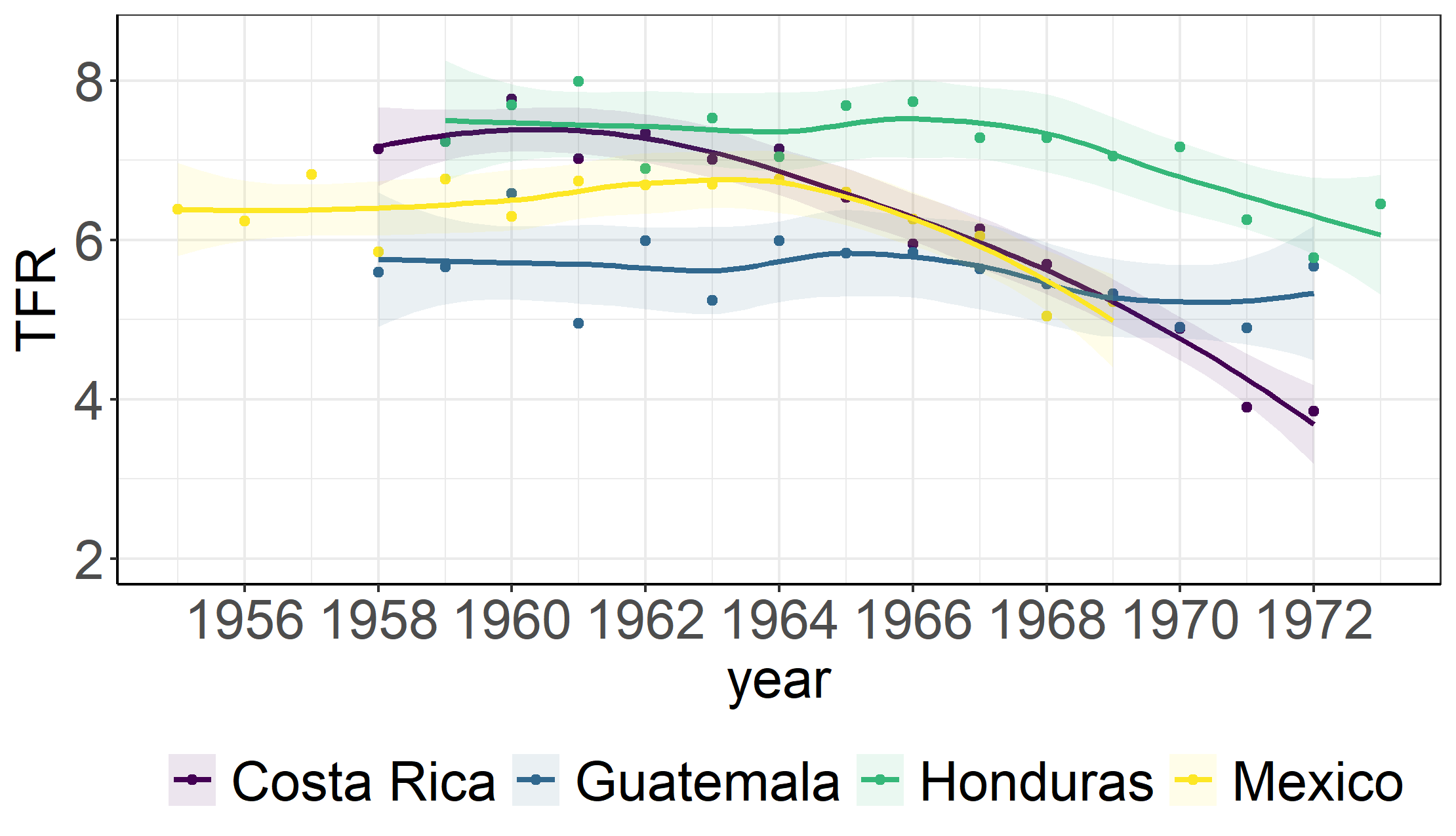

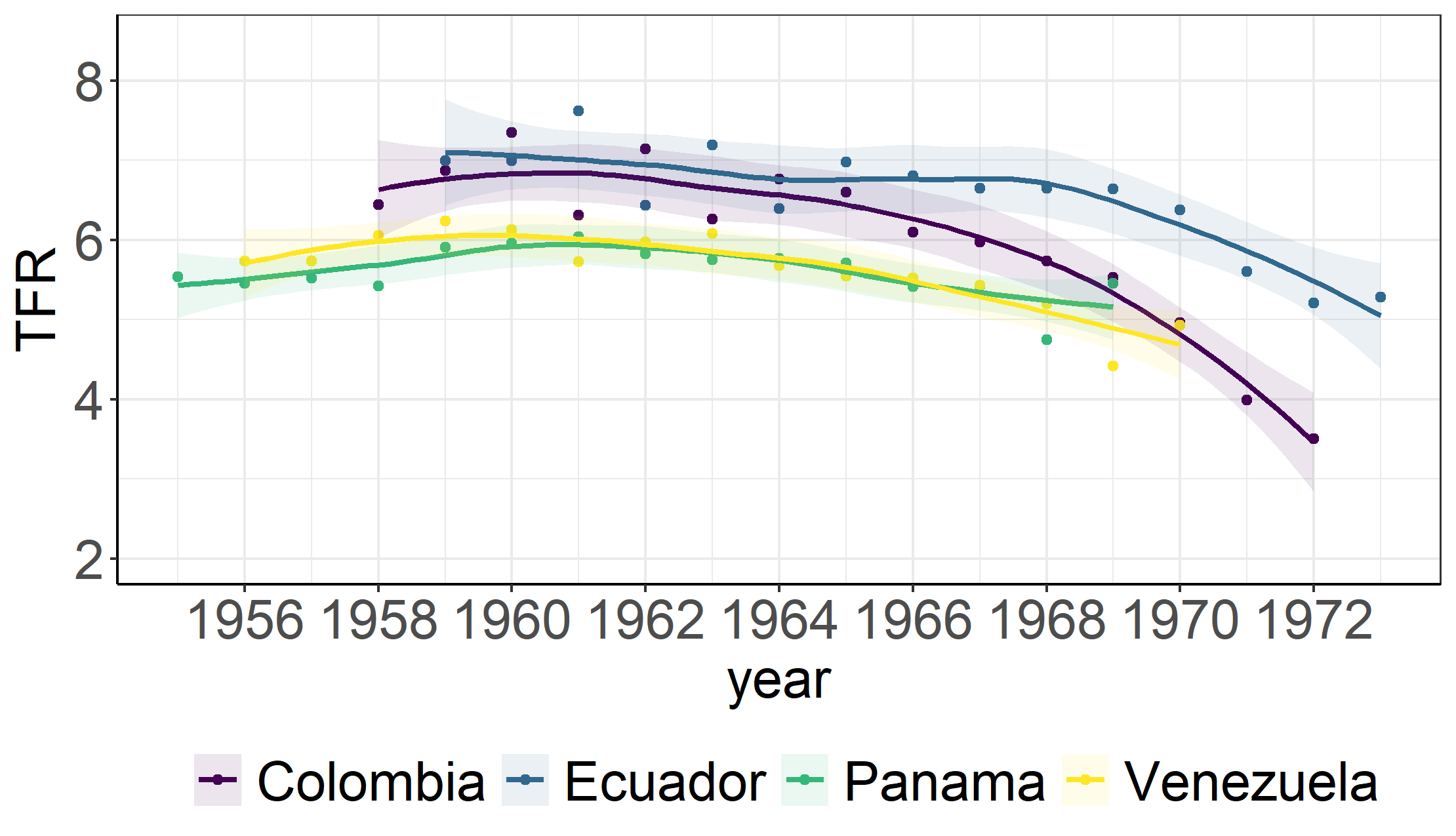

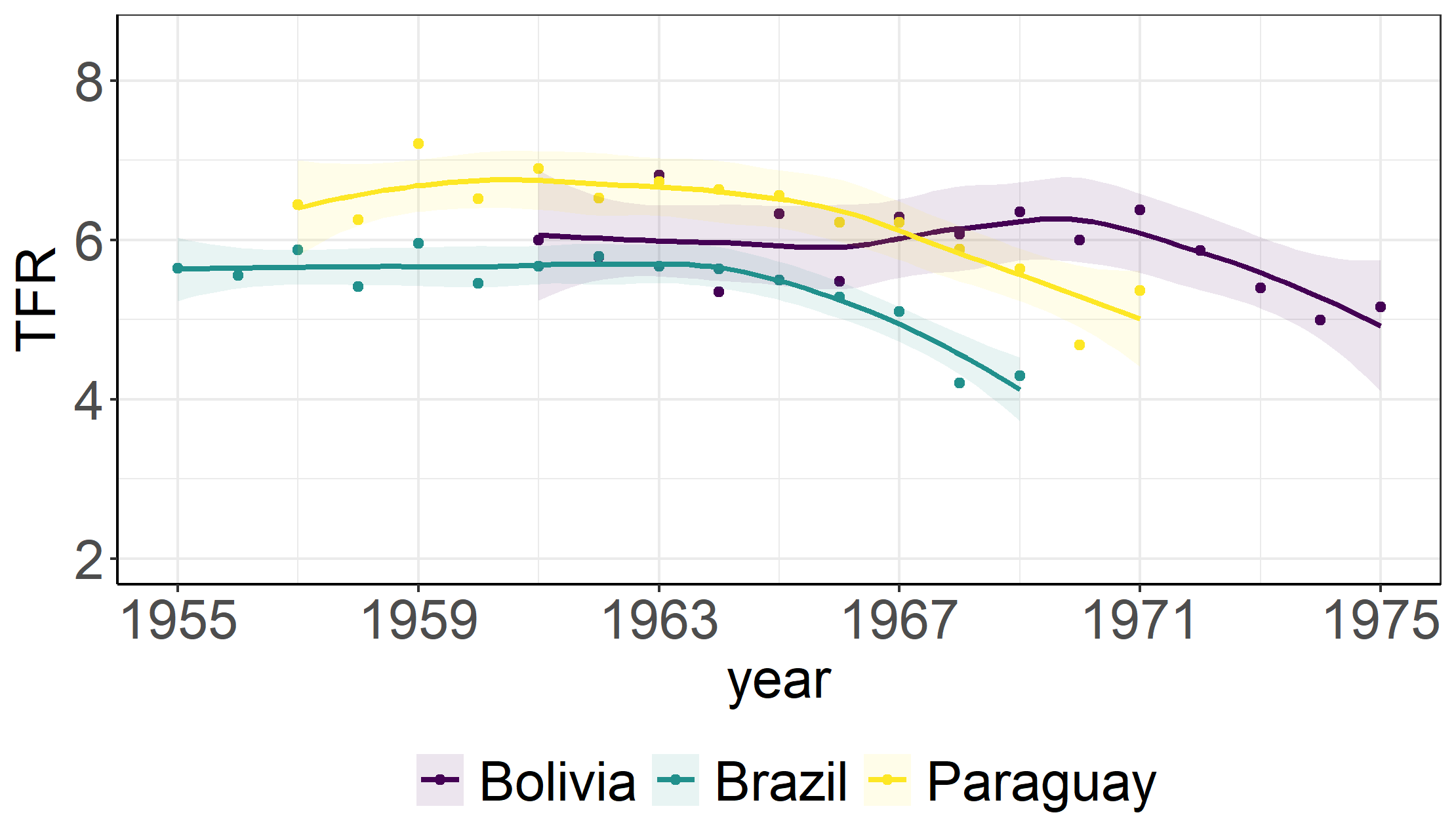

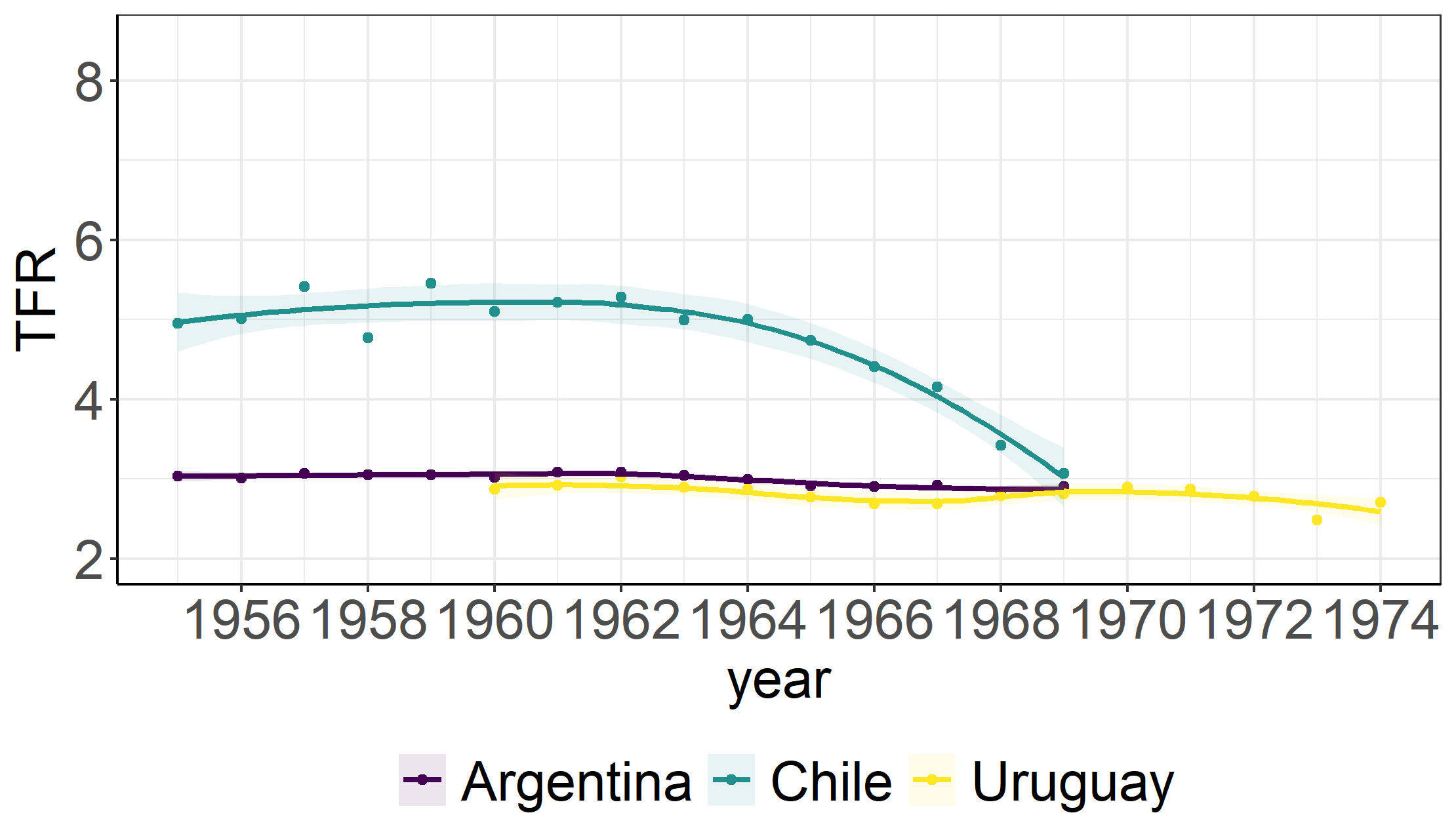

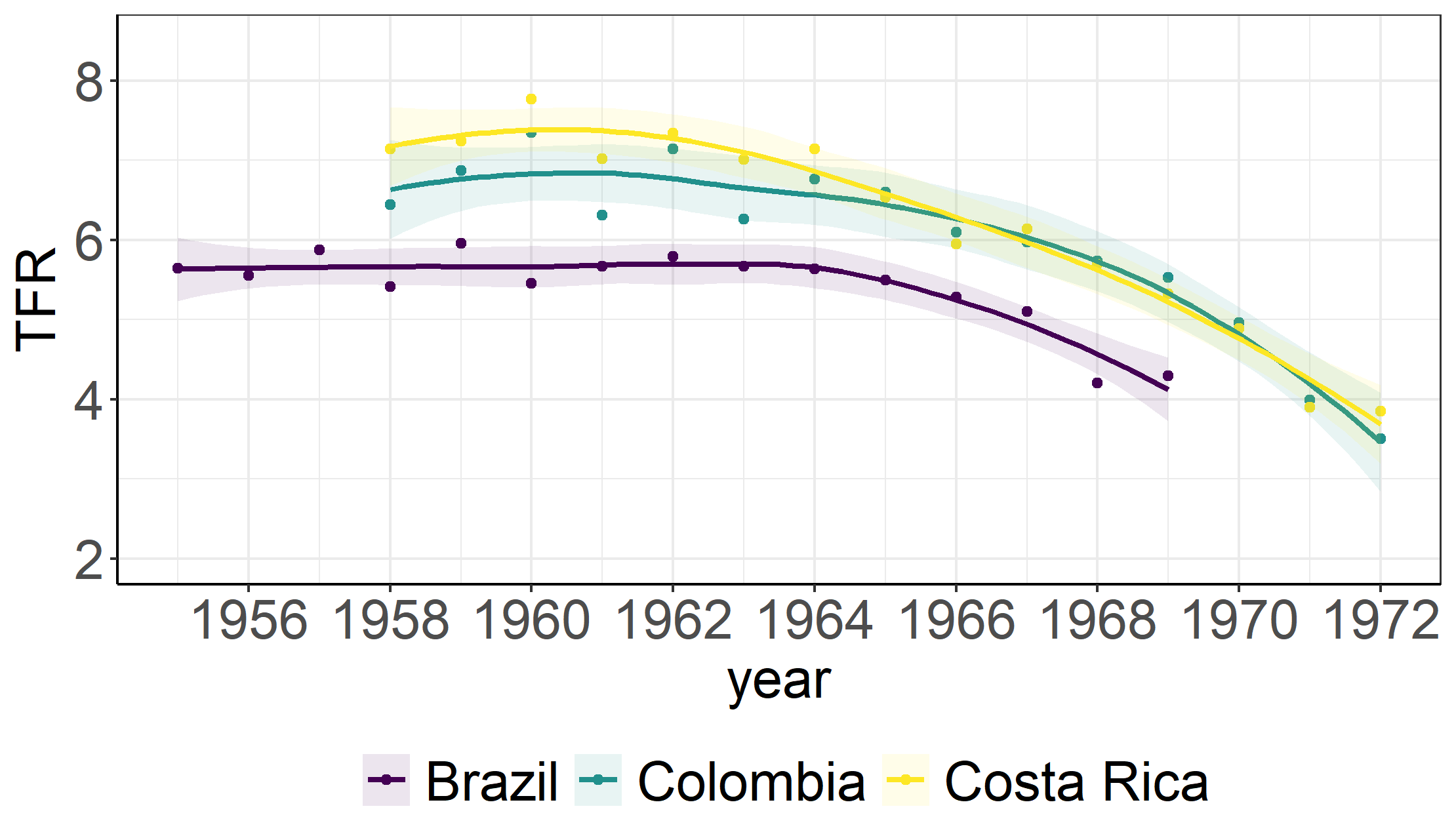

The Total Fertility Rate for each country is shown grouping the countries depending on their geographical location. The first group is the North and Central American countries. Although Costa Rica starts from the highest TFR, the country experiences the fastest and earliest decline in the group around 1962. The results from the two Caribbean countries show that the TFR estimations for Haiti are more volatile and less precise, which indicates that the quality of the census might be problematic. On the contrary, Trinidad y Tobago shows a steady decline after 1962, with small fluctuations. The countries that were part of the Gran Colombia (1819–1831) show considerable differences in the initial levels of fertility and also in the time and speed of the decline despite its geographical proximity and similar institutional legacies. Similar to Costa Rica, Colombia shows the first and the fastest fertility decline in the group. The countries located in the middle part of the South American region show similar levels of fertility until 1965 when Brazil and Paraguay experienced a steady decline. Not surprisingly the countries of the Southern Cone have the smallest fertility levels of all countries. In particular, in Argentina and Uruguay, the fertility decline started at the end of the 19th century, in a similar way as Northern European countries. Interestingly, Chile caught up by 1970.

Overall, the results confirm that despite differences in socioeconomic and cultural backgrounds, most of the Latin American and Caribbean countries in this sample experienced a fertility decline after the 1960s, with the exception of Guatemala and Panama that show a high and constant fertility level and Argentina and Uruguay that have small and constant fertility.

A rapid fertility decline: The case of Brazil, Costa Rica and Colombia

What explains the rapid fertility transition in Latin American countries? Despite these countries having differences in their socioeconomic and even cultural context, we see that overall fertility fell after the 1960s in almost all countries. A compilation of studies from CELADE and CFSC (1972) concluded that by 1964 sharp fertility differentials by education and socioeconomic status were evident in all metropolitan cities in Latin America and that the process of downward diffusion of family planning into the lower socioeconomic strata had begun. The ultimate reasons behind the fertility decline might vary across the continent, but it seems that most of them suggest the existence of interaction diffusion effects - although through different catalysts. I discuss briefly possible explanations taken from the literature for the cases of Brazil, Costa Rica and Colombia, which underwent a rapid fertility decline after 1964, before governments established an official population control policy.

Brazil

According to La Ferrara, Chong and Durye, the rapid fertility decline in Brazil had little to do with increases in education or an official population control. The education levels in the country increased slowly during the second half of the 20th century while advertising of contraceptive methods was illegal for some years (although according to Soto (1976) the beginning of organized family planning in Brazil started in 1966 but it was not until the late 1970s that the government invest in the diffusion of this information). La Ferrara et.al argue that a combination of new contraception methods and the spread of new family values (e.g. family size, the role of women in society) explain the rapid fertility decline. To test this, they measure the effect of exposure to soap operas on fertility, arguing that through these soap operas a new type of family was introduced for all Brazilians. They found that the expansion of the network broadcasting soap operas accounts for about 7% of the reduction in the probability of giving birth between 1980 and 1991.

Costa Rica

Similar to the results from CELADE and CFSC (1972), Stycos found two phases in the fertility transition in Costa Rica. First, urban women with superior education and higher socio-economic status followed by older, rural women with low socioeconomic status. In the second phase, after 1968, the National Family Planning programme played an important role. Rosero estimates that 25% of the decline in the total fertility ratio between 1968 and 1972 was due to the programme. By the end of the 1970s, all socioeconomic groups were adopting contraception. Rosero-Bixby and Casterline argue that social interaction had a causal effect in the rapid spread of birth control practices by looking at the spatial diffusion of the fertility decline. They conclude that the diffusion effects were stronger early in the fertility transition and that diffusion dynamics substantially accelerated fertility decline in Costa Rica before the National Family Planning was established.

Colombia

Colombia had one of the oldest and largest private family planning organisations in the world (PROFAMILIA), established in 1965 in Bogota. The effect of family planning provision in the fertility decline was addressed by Miller. His paper exploits the differences in timing and the geographical patterns of the spread of the family programmes and compares women living in cities that were exposed to the family planning programme at different ages. He finds that the rapid expansion of this private family planning program explains between 6% and 7% of the fertility decline in these cities between 1964-1993, an effect comparable to the one of La Ferrara et. al. for the case of soap operas in Brazil.

Conclusion

In this project I have shown how to calculate Total Fertility Rates for 16 Latin American countries using open-access data from IPUMS and Human Life-Table Database and publicly available code. The results confirm that despite differences in socioeconomic and cultural backgrounds, most of the Latin American and Caribbean countries experienced a rapid fertility decline after the 1960s. Looking at the cases of Brazil, Costa Rica and Colombia it is evident that the decline started before the introduction of a governmental population policy. Although the reasons why fertility started declining in metropolitan areas remain elusive, it is clear that the rapid decline is explained by different diffusion channels: either geographical, through private family planning organizations or through mass media. These channels diffused new attitudes and legitimate the concept of family planning spurring the fertility decline.