Human development and public services in Colombia

The world has seen an impressive and sustained increase in human development since the late 19th century and this trend has been accompanied by a steady decline in mortality rates. One of the most remarkable and puzzling aspects of these improvements in well-being is that they have been achieved even by countries with a late process of industrialization, which suggests that advances in living standards are not always reflected in the levels of Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Additionally, there is an ongoing debate in the literature regarding the determinants of the improvements in life expectancy throughout the 20th century. Recent contributions have highlighted the provision of public goods and the adoption of health technology as important explanatory factors, although the research is scarce for countries with a late process of industrialization and political modernization, such as Latin American countries.

Our research focuses on Colombia, which is of special interest because the country experienced enormous health gains during the 20th century despite growing disparities in per capita income. The country witnessed a rapid decline in mortality rates, dropping from 23.4 deaths per thousand inhabitants in 1905 to 5.5 in 2000. Consequently, life expectancy at birth increased from 35 years during the 1905–1912 period to 73 years in 2000–2005. But while life expectancy had surpassed 70 years, in 2005 nearly 60% of the Colombian population was living in poverty and extreme poverty. How did mortality change impact Colombians well-being over the long term? What explains the enormous improvement in life expectancy? Using a newly assembled dataset, we tackle these questions by constructing a new index of human development – the Historical Index of Human Development (HIHD) – covering almost two centuries for Colombia, and examined how improvements in water and sewerage systems provision led to a reduction of mortality in Colombia, in the same way as the literature found for advanced economies.

The Historical Index of Human Development

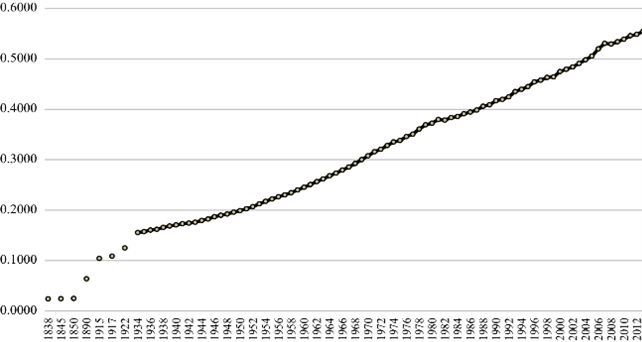

To understand Colombian well-being over the long term, we compute the HIHD for the period 1838-2013 by combining three key aspects of individuals’ well-being – income, education and health – into a synthetic value using a geometric average where all dimensions have equal weight. We use the GDP per capita in Geary–Khamis international dollars, at constant prices of 1990 for income, to adjust for inflation over time. For education, we use an index that joined information on literacy rates as well as primary, secondary, and tertiary enrolment rates. Lastly, we use years of life expectancy at birth as a proxy of citizens’ health. An added value of our indicator, as compared with the traditional Human Development Index, is that it takes into account the non-linear relationship between economic growth (in terms of GDP) and human development.

The results show a gradual and sustained improvement in well-being: the index for 1890 is almost three times that of 1838 and the levels for 2010 are more than five times those of 1915. The largest gains were achieved in the second half of the 19th century when the index grew 2.36% annually, and from the early 1950s to the end of the 1970s, when it grew 2.1% annually. However, after the 1980s the rate of improvement of the index slowed down, as seen in other Latin American countries. Overall, Colombia’s achievements in terms of human development were significant during the 20th century. However, these accomplishments were reached later than in developed economies. Even today, Colombia’s Human Development Index continues to lag behind that of developed economies.

What drove the improvements in human development in the long run? Decomposing the growth of the index into the contribution of its components, we found that health followed by education were the dimensions that contributed the most during 1838-2013. This implies that the reduction of mortality rates is a fundamental factor in understanding the history of progress in human welfare in Colombia. How was this reduction possible? Our hypothesis is that the reduction of mortality was largely brought about by improvements in the provision of aqueducts and sewerage.

The reduction of mortality and the role of public services

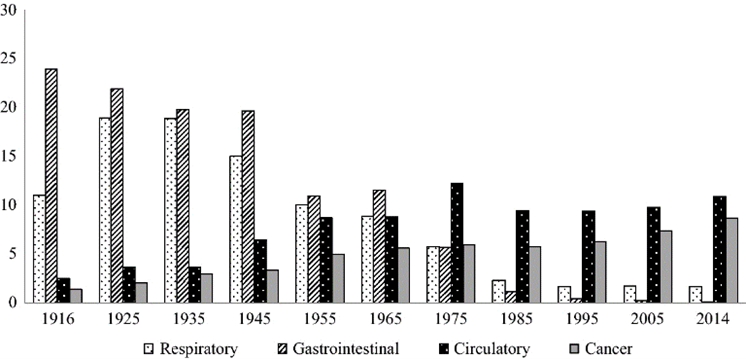

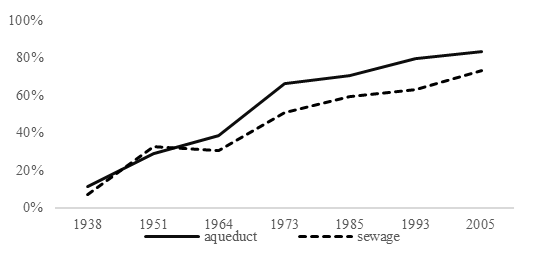

We construct a new dataset using statistics reported by the Colombian government, which included annual information on the main causes of mortality during 1916–2014 and the provision of sewerage and aqueduct services between 1938 and 2005. The mortality data in the next graph confirms the epidemiological transition in the country, where the percentage of deaths from tuberculosis, pneumonia, and gastrointestinal diseases decreased significantly throughout the century while deaths due to cancer and heart diseases have increased considerably in recent decades. The data on public services in the figure below show that since the middle of the century, the extension of aqueduct and sewerage services was considerable. A graphical analysis of the data shows no discontinuities in the fall of infectious diseases but rather a staggered process, suggesting that (a) the reduction in mortality did not happen suddenly from one year to the next because of the introduction of a drug or the adoption of a technology; and (b) that the speed at which the process takes place is similar to the speed with which the aqueduct and sewerage systems were installed.

Econometric results confirm that there is a negative and significant relationship between aqueduct and sewage provision and mortality rates. As expected, the largest effects of the expansion of this type of public service are on gastrointestinal diseases, mainly waterborne diseases. The effect of water and sewerage access on the total mortality rate and the respiratory disease mortality is lower than that on gastrointestinal mortality, especially in the case of sewerage services.

Due to data availability our estimations are based on the coverage of water provision instead of a precise measure of water quality, meaning that our results could be interpreted as a lower bound of the actual effects. Looking at data at the departmental level we observed that on average, achieving 50% coverage in aqueduct provision reduces gastrointestinal mortality by between 13 and 17%, while sewerage provision reduced the gastrointestinal mortality rate by 12%. The provision of public services affects the respiratory disease mortality only when 30% of households were provided with aqueduct and sewage, and deaths related to the respiratory system are reduced by 6.6 to 8.5% in the case of aqueduct and 4 to 5% in the case of sewage provision.

Achieving human development for all

Understanding the relationship between health and economic development is crucial to assess the mechanisms through which countries achieve improvements over time and to foster the design of contemporary policies, especially in developing economies.

For the case of Colombia, we show that the country improved the living standard of its population by greater public investments, especially aqueduct and sewage. However, by 2018 not all households in Colombia had access to these services. Departments like Chocó and Vaupés had less than 50% coverage in aqueduct and less than 30% of sewage coverage. In these departments, 10% and 18% of infant deaths are caused by gastrointestinal diseases. Our research suggests that improving the provision of water and sewage services in these departments could help reducing these numbers.

The paper can be found here